Sense and nonsense about safety behaviour and accidents at work

De meeste preventieadviseurs en arbo-professionals zien gedrag als hun grootste uitdaging. Niet onlogisch; immers, gedrag brengt nu eenmaal veiligheid tot leven. Zonder gedrag bestaat veiligheid enkel op papier. Alleen lijkt niet iedereen het met elkaar eens te raken over wat gedrag nu precies inhoudt, en al zeker niet wanneer het gaat over veiligheidsgedrag. Evenmin bestaat er overeenstemming over de vraag in welke mate ongevallen gedragsgerelateerd zijn.

Vooraf: de semantiek scherpstellen

Wanneer iedereen vertrekt vanuit zijn eigen premisse van (veronderstelde) definitie, zonder die vooraf klaar en duidelijk op elkaar af te stemmen, krijgt men al meteen een Babylonische spraakverwarring die niet in een-twee-drie opgelost raakt met wat over en weer getoeter op sociale media.

Al zeker niet wanneer bepaalde deelnemers aan de discussie van meet af aan vast gebetonneerd lijken in het grote gelijk van de eigen vooronderstellingen.

De discussie begint reeds bij de semantiek. Hebben we het hier over ‘gedrag als oorzaak van ongevallen’ of hebben we het over ‘gedragsgerelateerde ongevallen’?

Never trust your assumptions

Wanneer een fietser remt op een glad wegdek en daarbij ten val komt, kan de directe oorzaak van het vallen mogelijk worden toegeschreven aan het gladde wegdek, terwijl dit ongeval wel degelijk ‘gedragsgerelateerd’ is. Even het verschil opfrissen tussen ‘correlatie’ en ‘causaliteit’ kan daarbij nooit kwaad…

In die zin is een designfout in een technisch ontwerp evenzeer gedragsgerelateerd. Te beginnen bij het gedrag van de ontwerper en eindigend bij het gedrag van de medewerker die als gevolg van diezelfde designfout een ongeval overkomt.

Wat in bepaalde discussies eveneens als een onuitgesproken aanname naar voor komt, is dat sommigen de term ‘gedragsgerelateerd’ – al dan niet doelbewust – verwarren met ‘oorzaak van falen’ en daar in een beweging ook een verantwoordelijkheidsvraag willen aan verbinden. Quod non.

In een recente ‘discussie’ op sociale media die we vanaf de zijlijn volgden, was de bijdrage van Sim Doolaeghe (RiskConsulting) ongetwijfeld een van de meest genuanceerde reacties:

“Als aanvulling/nuance … De onderzoeken tonen aan dat ongevallen in 90% van de gevallen hun directe oorzaak vinden in een ‘menselijke handeling’, dit als een van de elementen binnen de multicausualiteit die eigen is aan een ongeval. Het is dus iets specifieker dan het gedrag. De grondoorzaken moeten we zoeken tot op het organisatorisch niveau. Hierbij is belangrijk een gedegen onderzoek te voeren, waarbij tijd en middelen niet altijd voldoende worden voorzien door de organisatie.”

De hoogste tijd dus om enige klaarheid te scheppen in deze zaak. Tenminste voor zij die bereid zijn deze boeiende materie onbevooroordeeld tegemoet te treden.

Gedrag: waarover praten we eigenlijk?

Volgens Van Dale gaat gedrag over ‘de manier waarop iemand zich gedraagt’. Veranderpsycholoog Dr. B. Tiggelaar houdt het nog eenvoudiger: ‘gedrag is datgene wat je kunt voordoen of kunt nabootsen’.

Veilig gedrag dan weer verwijst naar een norm op basis waarvan men gedrag als veilig of onveilig kwalificeert. Zonder dat dit iets zegt over het gedrag zelf.

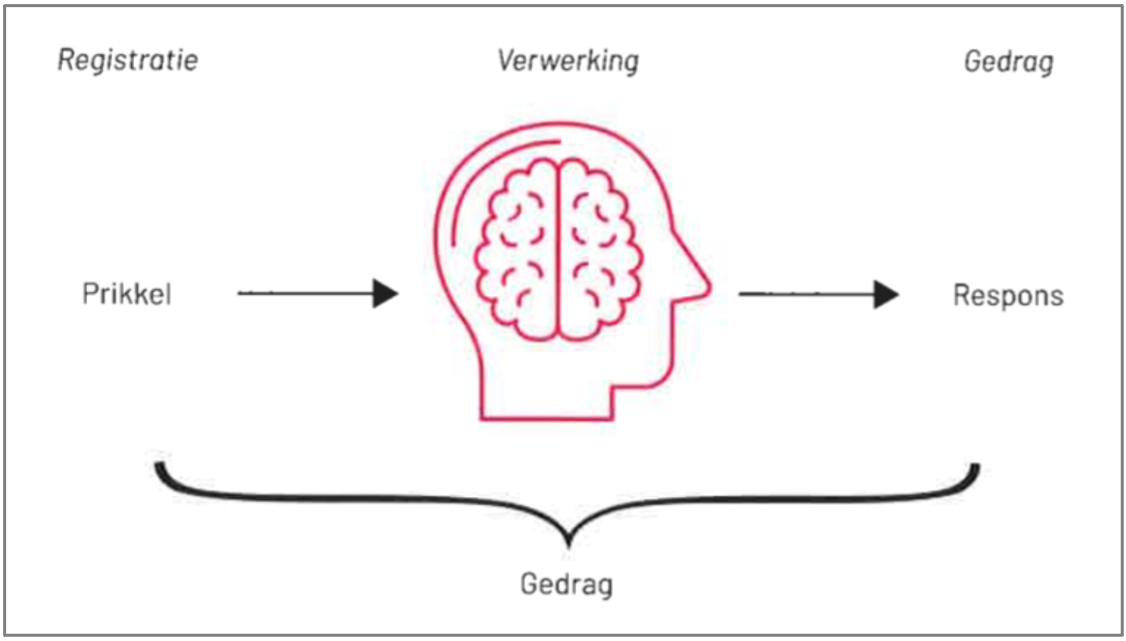

Volgens gedragsbioloog Prof. Marc Nelissen (2015) is het onmogelijk om gedrag te definiëren. Hij stelt dat gedrag begint met het registeren van een prikkel, een stimulus buiten het organisme dat de prikkel registreert. Het registreren is dus al gedrag. De mens verwerkt vervolgens deze prikkel. Ook dat is gedrag. En dan volgt er een respons: het zichtbare gedrag.

In die zin is elke verandering in de context voldoende om gedrag te initiëren, zodra er een mens is om deze verandering te registeren (Karl Weick, 1979).

[Grafiek ontleend aan Dr. Frank Guldemond; NVVK, Gedrag en veiligheid, 2018]

De gedragstheorie ‘old school’ versus de gedragstheorie ‘new school’

De gedragstheorie ‘old school’ (die binnen het bedrijfsleven nog steeds hardnekkig het veiligheidsdenken beheerst) gaat uit van de mens als rationeel denkend wezen. Een wezen dat zijn gedragsbeslissingen neemt op grond van een beredeneerde afweging tussen voor- en nadelen, tussen kosten en baten, tussen inspanning en veiligheid.

In het verlengde van deze zienswijze wordt veiligheidsgedrag gezien als het product van kennis en inzicht, vakbekwaamheid, procedures, instructies en supervisie. Veiligheidsgedrag, een kwestie van gezond verstand dus. Waar hebben we dit de laatste tijd nog gehoord?

Eveneens kenmerkend voor deze visie, is dat er in het kader van een arbeidsongeval al te gemakkelijk gedacht wordt in termen van ‘gedrag als oorzaak’ => ‘ongeval als gevolg’, terwijl de werkelijkheid heel wat complexer is, namelijk ‘gedr ag als result ante van een veelheid aan interne en externe prikkels’ (zie verder).

In de ‘old school’-visie kiest men bij voorkeur voor het bijsturen van onveilig gedrag door middel van bijkomende (cognitieve) opleidingen, door het aanscherpen van procedures, door het inzetten op toolboxen en LMRA’s, door postercampagnes, … De lijst met voorbeelden is wat dat betreft onnoemelijk lang.

Dit alles geschraagd door een sterke (high energy) operationele discipline. Want dat mag toch worden verwacht van medewerkers, zo klinkt het dan.

Wanneer aan alle randvoorwaarden is voldaan, werken mensen – gestuurd door hun ‘gezond verstand’ – van nature veilig. ‘Safety behaviour by nature’ dus.

Wat de meesten reeds intuïtief aanvoelen, is inmiddels ook uitvoerig onderbouwd en bewezen.

Consultant tegen klant: “Wist je dat gedrag van mensen grotendeels onbewust gebeurt?” Klant: “Echt waar? Daar heb ik nu nog nooit iets van gemerkt!”

Een belangrijke ommekeer die de theorie ‘old school’ onderuithaalt, kwam in 2002 met Daniel Kahneman [Nobelprijs-winnaar 2002; Dual System Theory]. Verder bouwend op de inzichten van Kahneman kreeg Thaler in 2017 vervolgens de Nobelprijs voor zijn onderzoekswerk rond ‘nudging’. Samen vormen ze in belangrijke mate de pijlers van de gedragstheorie ‘new school’.

De gedragstheorie ‘new school’ gaat ervan uit dat het gedrag van mensen grotendeels onbewust wordt aangestuurd.

De Dual System Theory maakt namelijk onderscheid tussen twee gedragssystemen in de hersenen: een rationeel systeem dat bewust gedrag produceert en een emotioneel systeem (of limbisch systeem) dat automatisch gedrag produceert.

Onbewust aangestuurd of automatisch gedrag maakt ten minste 95% uit van ons gedrag. Wetenschappelijke bronnen zijn hierover unaniem: Ondermeer Kahneman (2002), Bargh (2004), Tiggelaar (2005), Baumeister (2006), Dijksterhuis (2009) laten vanuit een verscheidenheid aan empirisch en klinisch onderzoek eenzelfde geluid horen.

In de gedragstheorie ‘new school’ wordt gedrag gezien als het product van emotionele drijfveren en prikkels vanuit de omgeving.

“We worden in hoge mate gestuurd door volledig automatische processen in de hersenen, waar we geen controle over hebben, en we hebben niet eens door dat we zo functioneren.” [D. Kahneman; Thinking fast and slow, 2011].

Vanuit evolutionair oogpunt is het emotioneel systeem het oudste systeem: geprogrammeerd in de oertijd, vertoont het alle kenmerken van onveilig gedrag. Niet in het minst omdat het limbisch systeem (onder meer) bij voorkeur kiest voor de weg van de minste inspanning, kritiekloos waargenomen gedrag kopieert, risicotolerant is, behoren tot de groep belangrijker vindt dan veilig werken, snel went aan onveilige situaties en niet of nauwelijks geconnecteerd is met het cognitieve deel van ons brein.

Vanuit deze nieuwe zienswijze wordt onveilig gedrag vooral bijgestuurd door het ontwikkelen van nieuw aangeleerd veilig gedrag. Waarbij het gedragsontwikkelproces loopt langsheen het pad van cognitie (weten wat en hoe), vaardigheid (kunnen), competentie (toepassen in eenvoudige situaties) en finaal autonoom toepassen in de praktijk (vakbekwaamheid). Dit alles geschraagd door de nieuw ontwikkelde (low energy) veilige operationele routines.

Enkele interessante uitgangspunten: het reflecteren waard

Ontleend aan publicaties van onder meer veiligheidspsycholoog Juni Daalmans (De breingids, 2011) en van Prof. R. Long (2014) zijn hiernavolgende uitgangspunten met betrekking tot veiligheidsgedrag ‘new school’ op zijn minst verhelderend:

Uitgangspunt 1:

Alle gedrag komt voort uit het brein. Gedrag is in de regel onbewust en wordt gegenereerd door onze automatische piloot.

Uitgangspunt 2:

De meeste veiligheidsovertredingen gebeuren onbewust en zijn het resultaat van interne of externe drijfveren. Gedrag is daardoor veranderlijk en situationeel bepaald.

Uitgangspunt 3:

Automatismen zijn vele malen sterker dan verstandelijke inzichten. Een regel of voorschrift leidt niet vanzelf tot overeenkomstig gedrag.

Uitgangspunt 4:

Veilig gedrag ontstaat wanneer mensen een besef hebben van risico’s, naast de vaardigheden om ermee om te gaan. Dit kan alleen als mensen beschikken over het juiste aangeleerd gedragsrepertorium.

Uitgangspunt 5:

Het aanleren van nieuw/veilig gedrag is het resultaat van inzicht, model-leren, motorisch leren en feedback op het vertoonde gedrag.

Uitgangspunt 6:

Sociaal leren [model-leren] is het sterkste mechanisme in het aanleren van (on)veilig gedrag. Management en informele leiders zijn de belangrijkste modellen.

Uitgangspunt 7:

Mensen zijn van nature risicotolerant en zijn standaard te positief over hun veiligheidsprestaties. Deze vorm van zelfoverschatting leidt tot het hanteren van minder veiligheidsmarges, met alle mogelijk nefaste gevolgen van dien.

Uitgangspunt 8:

Mensen willen graag bij het team behoren en zijn bereid hiervoor concessies te doen. Een onveilig handelend team kan mensen verleiden tot onveilige handelingen welke ze in hun eentje nooit zouden stellen.

Dat mensen in werkelijkheid meestal niet uitsluitend rationele en beredeneerde keuzes maken, is op zich niet nieuw. Wel nieuw is dat de spagaat tussen het beeld dat men er doorgaans van heeft en de werkelijkheid, vele malen groter blijkt dan oorspronkelijk gedacht.

Er gaapt een gigantische kloof tussen de meest actuele kennis over menselijk gedrag en de mate waarin die kennis wordt gebruikt bij het vorm en gestalte geven aan een veiligheidsbeleid. Een betere kennis van wat het werkelijke veiligheidsgedrag allemaal beïnvloedt, kan nochtans in sterke mate bijdragen tot een meer doeltreffende veiligheidsaanpak.

[Veiligheidscultuur 4.0 – de nieuwe werkelijkheid; Anne-Marie Vanhooren, 2020]

Individueel gedrag of groepsgedrag: twee verschillende werelden.

Mensen hebben zowel een ‘eigen identiteit’ als een ‘sociale identiteit’ die er totaal anders kan uitzien. Gedrag in een groep is anders dan wanneer mensen alleen zijn. Daarnaast kunnen mensen zich in de ene groep anders gedragen dan in een andere groep.

Het gedrag van mensen in een werkcontext wordt beinvloed door verschillende variabelen. De veldtheorie van Lewin stelt dat het gedrag van mensen een functie is van de interactie tussen hun karakter enerzijds en de situatie anderzijds. Dit laatste wordt meestal kortweg ‘de omgeving’ genoemd.

Samengevat komt Lewin’s veldtheorie hierop neer: het veiligheidsgedrag van mensen wordt bepaald door:

• wat ze zelf willen

• wat ze kennen en kunnen

• wat de omgeving van hen afdwingt

• wat de beschikbare middelen mogelijk maken

Interessant is dat dit model in grote mate wordt ondersteund door de indeling van groepsdeterminanten van de Nederlandse Raad voor Leefomgeving en Infrastructuur (Rli). Het gedragsmodel Rli (2014) weerhoudt vier clusters: (1) bekwaamheden, (2) motieven, (3) omgeving, (4) keuzeprocessen.

Dit resulteert in onderstaand model:

Elke cluster van dit model bevat op zijn beurt verschillende gedragsvariabelen die in mindere of meerdere mate het veiligheidsgedrag op de werkvloer beïnvloeden. En zo is alles met alles verbonden; en zo is elk ongeval dan ook op een of andere manier gedragsgerelateerd. Tot spijt van wie het benijdt.

In een volgende bijdrage gaan we dieper in op de verschillende gedragsvariabelen die dit model tot een ijzersterk onderzoeksmodel maken met betrekking tot de gedragskant van een ongeval of incident.

Bij minstens 90 procent van de arbeidsgevallen is menselijk gedrag in het spel. Gedrag is het resultaat van de interactie tussen het individu en zijn omgeving. In die zin is het overgrote deel van de arbeidsongevallen gedragsgerelateerd.

Een analyse van de oorzaken van een arbeidsongevallen daarentegen is heel wat complexer.

Op het niveau van het individu spelen zowel bewuste als onbewuste besllssingsprocessen een rol, in een belangrijke mate aangestuurd door zijn rationele competenties en zijn emotionele drijfveren.

Met betrekking tot de interactie met de werkomgeving komen gedragsprikkels vooral vanuit enerzijds de brede werkomgeving (zoals het team, de fysieke werkcontext, de socio-culturele omgeving, de heersende veiligheidscultuur, …) en de onderneming als geheel (bedrijfscultuur, waarden, normen, rol en positie van HSE, …).

Tot slot, gefaciliteerd vanuit de brede werkomgeving: de beschikbare arbeidsmiddelen en de immateriële ondersteuning (zoals opleiding, coaching, machtsafstand,…)

Conclusie: het grootste aantal arbeidsongevallen is weliswaar gedrags-gerelateerd, echter de oorzaken van diezelfde arbeidsongevallen moeten meestal dieper in de organisatie worden gezocht.

[Auteur: W.J. Wastyn]

READ MORE